As the farmers’ protest entered the eighth month, social media is again abuzz with loads of arguments in favour and against the agitation. While both parties have a lot to argue about the pros and cons of the three Bills the farmers are protesting against, many are silent on their impact on the “common” farmers.

What is meant by “common” farmers? The term “common farmer” refersto the farmer whose land holding is less than 5 acres. Interestingly, around 85 percent of the country’s farmers fall under this category. To talk about their struggle and the challenges they encounter, let us understand some basic realities. The table below gives a fair idea about

this category of farmers.

| Land Holding | % of House holds | % of Land hold |

| Land less | 11.24 | |

| Sub-margin holdings (0.01 – 0.99 acres) | 40.11 | 3.80 |

| Marginal holdings (1.00 – 2.49 acres) | 20.52 | 13.13 |

| Small holdings (2.50 – 4.99 acres) | 13.42 | 18.59 |

| Medium holdings (5 – 14.99 acres) | 12.09 | 37.81 |

| Large holdings (15 acres + above) | 2.62 | 26.67 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 1: Distribution of Land

Source: Table 1 of the Fifth NCF Report based on Some Aspects of Household

Ownership Landholdings-1991-92. NSS Report-399

The 72 percent of the Indian farmers who own land equal to or less than one hectare are the common farmers. One hectare is equal to approximately 2.47 acres of land. The productivity of agricultural land is calculated in India by the yield of each hectare of land.

As per the 2019 data, the average productivity of rice per hectare of land is approximately 2,600 kg while for wheat, it is around 3,500 kg. Thus, the total capacity of a common farmer to produce wheat or rice is a maximum of 3,500 kg in a crop season. Assuming he/she harvests it twice a year, the annual production would come to approximately 7,000 kg.

Supposing a farmer has five members in his family whose staple diet is rice. Assuming they consume approximately 2 kg rice per day, it comes to 800 kg rice consumption in a year.

This will leave the farmer with only 6,200 kg for sale. At the current MSP rate of Rs 1,940 per quintal, his earnings from the 6,200 kg rice for the year will be around 1.2 lakh. This learning will be marginally more for farmers who are producing wheat as wheat production is slightly more per hectare, but the MSP more or less remains the same.

With this earning, the farmer not only has to bear the cost of farming but also meet his family’s expenses apart from saving for investment in other major milestones of his life.

This is where the fight for financial management starts. In the absence of well-structured reliable credit schemes, chances are the farmer will be caught in the vicious cycle of loan and repayment and eventually end up in a debt trap. Though banks offer loans under various government schemes, the problem lies in documentation and awareness.

Hence, a loan from the unorganised sector comprising money lenders like “artiyas” and “local baniyas” who extend financial support to these farmers in their hour of need on the basis of trust and personal relations is the ground reality. Since it is an unregulated sector, the terms of the credit are also subjective and are often loaded against the farmer.

What’s more, most of such disadvantaged farmers are not educated enough to access the latest farming technology. Also, dependence on rains in the absence of a proper irrigation system adds to the challenges of these farmers. What then are the alternatives available to improve a lot of these farmers so that they do not end up in a debt trap that eventually results in suicides.

Option1: Increase productivity of the existing piece of land even though this too has limitations. The highest productivity at this point of time across the world is around 6,800kg per hectare for rice. This means the productivity can be doubled but then it requiresa huge investment in preparing the land and using the modern means of cultivation.

Option 2: Diversify the crop. Instead of depending on rice and wheat crops, the farmers can look to producing cereals that could generate more revenue. But this requires giving up the safety net of MSP and exposing them to the market risks. In most cases, the farmers won’t be in a position to take the risks. In fact, those farmers who expose themselves

to risks find place emerge as success stories in farming.

Option 3: Diversify land usage to other activities like beehives, poultry, fisheries etc. But this again is a venture fraught with risks as it requires giving up the safety net of the MSP and other subsidies and working towards acquiring new knowledge and skills.

Option 4: Create more and more cooperative societies where themarginal farmers can pool in their land and resources and enjoy higher bargaining power as well with risk-taking appetite. But this requires change in the mindset, development of infrastructure, pumping of fund and above all, knowledge and conviction in the farmers to tread this path.

Option 5: Get into export market as India has a variety of land types and weather conditions to support production of a wide variety of crops, cereals, flowers etc. However, the data shows that despite surplus production in wheat and rice, Indian exportsshow a declining trend. This is because most of our crops do not meet criteria for export prerequisites. To ensure that the produce meets the international standard, a lot of investment must be made to prepare the land and soil to reduce the pesticide usage and type of pesticides used. This again is a challenge area for the common farmer.

In the light of the above challenges our farmer faces, if one were to evaluate the three farm Bills a section of farmers wants to be withdrawn, they will have a negligible or minuscule impact on the challenges of the common farmers.

While addressing the issues of the farmers, one shouldn’t forget that a large part of the subsidies is cornered by just 1 percent of the affluent farmers who can leverage the benefits of the governmental policies to their advantage. This is the elite group that earns in crores yet enjoys the exemption from all mandatory taxes the government extends to farmers.

Aren’t they a burden on the taxpayers?

Against this backdrop, the points to ponder over the ongoing farmer stir

are:

1. Which section of farmers do these protestors represent?

2. Is it not the time that the categories of farmers are redefined?

3. Who will benefit the most from the withdrawal of the farm Bills?

4. Shouldn’t the government adopt policies that could address the issues

of all the sections of the farmers?

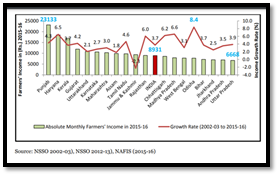

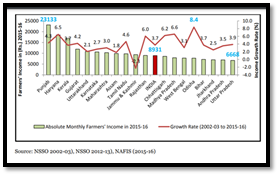

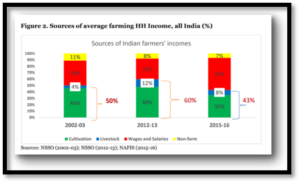

The three tables/graphs inserted in the article have been sourced from:

1. M S Swaminathan Report– National Commission on Farmers.

2. A CASI (Centre for Research Paper on India, University of Pennsylvania)

working paper on “Reforming Indian Agriculture”. The original source of

the data is NSSO.

Disclaimer: We do undertake rigorous checks on content provided by contributors before publishing the same. If you come across some factual errors, kindly bring this into our notice and we shall review your objection and claim as per our policy and display correction credits and corrections on the article itself.

The opinion expressed in the article is of the writer. Writer is a freelance journalist/journalist based in Delhi