[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

With the unlocking process starting migrant labourers began to return to cities. These labourers had left the cities in the wake of severe lockdown imposed by the government to contain COVID-19.

With this, metropolises like Delhi are again abuzz with commercial activity. They had left the cities because they had no job at and no money in their pocket. Now, they are returning because they have no earnings at the villages too. They had hoped to eke out a living back home, but they were disappointed as they could not find a worthwhile job to sustain them economically, hence the reverse exodus.

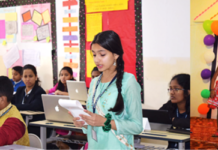

Kiran, a cook who spent more than 10 years in Delhi, left for her village in Bundelkhand with her husband, a construction labourer, and two children in June. But she had to return to Delhi in September after three months of stay at her village.

Sharing her bitter experience, she said, “We went to the village with the hope that we could be able to do something there and at least save our lives from the pandemic. But it did not happen as per our plans as we had to live without work.”

During their stay at home, she said, “We exhausted all our savings and had to borrow money for food and return journey. Now that I am back in Delhi, job opportunities have shrunk drastically. Earlier I was working for 10 families, but now I could manage to get work at only two homes. My husband too stays at home most of the time due to lack of work. How long can we survive this way,.”

These labourers complain that people are still reluctant to hire their services as the fear of Covid is still lurching on their minds. What is all the more worrying for these hapless people is that at a time when their income has nosedived, they have to spend money on precautionary measures to ward off the disease which they rue is an additional financial burden on them.

Ramesh Paswan, a labourer from Gaya, said, “Masks, sanitisers and the stringent terms laid down on commuting have added to our financial liability. A major portion of what we earn today we spend on such things. Unless things are normalised life to the level of pre lockdown days, life is in Delhi will remain harsh for the labourers. We are poor, so are left with no option but to return and search for job for a livelihood.”

The nature of migration during Covid crisis and then the return to their place of livelihood is something that has exposed the policies and the planning of the governments. Be it state or the Central governments, all have miserably failed to handle the crisis arising from the pandemic to the detriment of the poor and the downtrodden. The hardest hit of all are the labourers who are left to fend for themselves for survival with no succor forthcoming from any quarters.

In the context of migrant crisis, Dr Shreesh K Pathak, a political analyst and assistant professor II at Amity Institute of International Studies, Amity University, Noida, described the phenomenon of migration as unavoidable. “As cities cannot be in a dynamic existence without the continuous support of villages and satellite areas the waves of in-migration from villages and to towns to cities are inevitable, which are often appreciated,” he explained.

“How these incoming pools of in-migration are being accommodated often,” he said, “is evident in the daily life of our cities especially in metros.”

Borrowing analogy from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs which includes five layers of need, individuals who come from different corners of the country to the cities try hard to climb first layer of physiological needs to fulfill their primary needs of air, water, food, sleep, clothing, shelter and reproduction. Few of them anyhow could also try to acquire the second layer of needs which consists personal security, employment, resources, health, and property.

This forced migration of labourers, small crossroad shopkeepers, struggling amateurs and small-scale entrepreneurs from the city clearly shows that irrespective of what they have contributed to formal and informal economy of the country, they have been alighted down from their second and first layer of need hierarchy ladder to the uncertain chaos.

Amidst all this, the essential intervention of the state is missing and unfortunately many from so far unaffected strata are not even recognising this missing intervention by the agencies of the state.

At this juncture, the role of the state must be scrutinised. In the gradual transition of the state from the era of classical liberalism to the notion of welfare state, the scope of the state is continuously expanding to almost all possible aspects of human life. As citizens we are continuously allowing the interventions of the state in our different dimensions of life only in the expectation that the state would play its positive role and cater to all that our needs.

If at this hour of crisis, the thick periphery of the Indian republic is found unable to preserve even a pinch of hope for the future, this is construed as a failure of the state. Eventually, it would invite inherent pressures to the state security complex of the country, too.

Renowned security academician, Barry Buzan, in his book titled ‘People, States and Fear’ pointed out that “security is not just about the states but related to the all human collectivities”. Out of five factors he defined as decisive for the maintenance of security of the state, the three – political, social, and economic – are being seriously affected by this poor management of returning labourers and workers.

“These waves of in-migration without hope are detrimental to the state and it urgently requires highlighting the responsibility of the different stakeholders of the agencies of the state,” he concludes.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Disclaimer: We do undertake rigorous checks on content provided by contributors before publishing the same. If you come across some factual errors, kindly bring this into our notice and we shall review your objection and claim as per our policy and display correction credits and corrections on the article itself.

The opinion expressed in the article is of the writer. Writer is a freelance journalist/journalist based in Delhi